Reflecting the blue skies above, the Jordan Gate towers are the tallest — and arguably the emptiest — buildings on the Amman horizon. King Abdullah II in 2005 laid the foundation stone for the prestigious project, which was said to become the business address in the Hashemite Kingdom. Since 2009 however, the two giant cranes standing next to the towers have remained idle. The top floors have never been built and part of the glass exterior has come off. Today, the $300 million project remains a grim reminder of the days when the sky seemed the limit for Amman real estate.

The Jordan Gate was an initiative of the Gulf Finance House (GFH), a Bahrain-based investment firm badly hit by the 2008 financial crisis. GFH needed a $300 million loan to stay afloat and in 2010 escaped default only by agreeing to postpone the final repayment of $100 million. According to a prominent Jordanian contractor, who wished to remain anonymous due to fears public comments could jeopardize his business, GFH was not able to pay Al Hamad Contracting (AHC); instead, it offered the Sharjah-based firm the unfinished towers. Executive asked GFH and AHC to comment, but both declined.

“What happened is simple: the bubble burst,” said Wael Jaabari, owner of the large Jordanian real estate agency Abdoun Real Estate. “The developers had a business plan based on selling office space for some $4500 per square meter (sqm), which was, perhaps, feasible before the 2008 credit crunch. Yet they better get used to the new reality and swallow their losses. Maybe they can still rent out part of the building.”

“Compared to the peak prices of early 2008, prices in west Amman, depending on a property’s location and quality, have decreased by some 25 to 60 percent, while prices in the outskirts have decreased by some 80 percent,” said Jaabari. As an example, he refers to his office in Abdoun, a prime location, which he bought in 2010 for $1,200 per sqm, while a few years back people were paying up to $3,000.

And yet the Jordan Department of Lands and Surveys (DLS) last January reported that the real estate market grew by 8 percent in 2011 to amount to nearly $9.8 billion, following a 25 percent increase in 2010. Hopeful signs of recovery, although the increase follows upon a decline of more than 30 percent in 2009 alone. When compared to 2007, the 2011 market is only 14 percent larger.

There are other reasons to treat the DLS statistics with care. “One government measure to boost trading was to abolish the real estate registration fee of some 10 percent,” said economist Yusuf Mansur, chief executive officer and owner of Jordanian consulting firm EnConsult. “Today, a government employee estimates the value of a property or land, which is generally higher than what the contract states. What’s more, the sales of a small number of commercially viable plots of land boost and obscure the overall picture.”

Boom & Burst

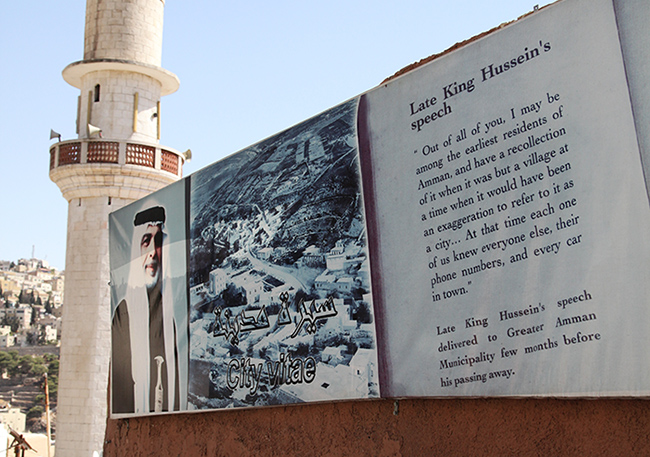

View on Amman

The reasons behind Jordan’s real estate boom prior to the crisis are well known. The 2003 United States-led invasion of Iraq forced many Iraqis to flee to Jordan. Some arrived, quite literally, with suitcases full of money, which they used to buy homes in Amman’s affluent western section. Price increases of up to 400 percent were recorded and real estate trading increased by a whopping 74 percent and 48 percent in 2004 and 2005, respectively. The Amman market was awash with cash and seemingly everyone wanted a piece of the pie, including many foreign investors. An ABC Investments report states that 1,247 new construction companies were established between 2004 and 2008, of which 339 companies were established in 2008 alone.

Today, the days of plenty seem long gone indeed, if only for the fact that loans are not as easy to come by. The Central Bank has imposed a strict ceiling of 20 percent of customer deposits on the amount of facilities granted by banks to the real estate and construction sector. “Banks are less lenient regarding real estate loans,” said Jaabari. “For a while, they permitted firms to postpone payments. Pay a bit now, a bit later. Now they just want their money. As a consequence, we no longer have pinball property development. No more building to speculate and sell; it’s a buyer’s market.”

The Jordan Gate project was not the bubble’s only victim. The GFH initially also intended to build the $800 million Royal Village — a project that never saw the light of day. The same is true for The Living Wall, a project that is anything but alive. An enormous billboard still reminds Amman of the six luxury towers and Buddha Bar that were set to arise. In 2006, the project was even named Best Future Commercial Project at Cityscape Dubai. Today it remains a huge hole in the ground.

The Living Wall was the brain child of Mawared, a state-owned developer with close ties to the military, which has been tainted by a series of corruption scandals. Its former CEO, Akram Abu Hamdan, has been detained for allegedly pocketing millions of dollars.

Dubai World’s Limitless Towers did not even dig a hole. A massive marketing campaign prior to the crisis stressed the towers’ height: at 200 meters they would dwarf even the Jordan Gate, while the suspended swimming pool, at 125 meters, would be the world’s highest — would being the operative word, as the $300 million project was never even started.

Another failure concerns the $1 billion Saraya Aqaba resort. Construction started in 2006, yet has been stalled since 2008. Saraya Holdings, largely owned by former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, also planned to build a $700 million Dead Sea resort. Announced with much fanfare at the 2007 World Economic Forum, construction never started. The same is true for the company’s regional projects. Small wonder therefore that the Saraya Holdings headquarter, which Hariri planned to build at his brother Bahaa’s Abdali Project, has been stalled as well [see box].

Abdali stays Afloat

In 1920, some 5,000 people lived in Amman. By 2012, some 2.5 million.

“The Abdali Project was not spared the effects of the global financial crisis like so many other large, mixed use developments,” said Salim Majzoub, deputy CEO of Abdali Investment and Development. “Since the start of the crisis, not a single investor has pulled out; however, construction work on some of the projects was halted for a period of time. Currently, some 15 percent of the developments in ‘phase one’ are on hold.”

With an estimated cost of $3 billion, the first phase of the Abdali Project foresees, among other elements, the construction of 12 mixed-use buildings and a shopping boulevard and mall, which are the heart of the 1.7 million sqm regeneration development in central Amman. The project is a joint venture between Jordan’s Mawared and Horizon, a Lebanese property developing firm established in 2002 by Bahaa Hariri. Both Mawared and Bahaa Hariri own 44 percent; the remainder is in the hands of Kuwait Projects Co.

As a forest of construction cranes continue to operate at Abdali, the project seems to have survived the onslaught that followed the 2008 crisis. “Approximately 75 percent of the mid-rise developments within the project will be ready for opening in 2012,” said Mazjoub. “They mainly consist of ‘Grade-A’ commercial and luxury residential space. The Abdali Boulevard has been over 80 percent completed and construction has started on the Abdali Mall, which is due to become operational by the end of 2013.”

Since 2008, the project has received several loans from Arab Bank, BLOM Bank and Bank Audi, with work underway on a number of banks’ offices, as well as offices for Saudi Arabia’s Rajihi Cement and Lebanon’s MedGulf. Also, five towers are being built, among which are the Rotana Hotel Tower (“the highest in the Kingdom”) and a DAMAC residential tower. The Emirati developer reportedly faced some financial woes, yet found new partners to complete the 34-story building, though abandoned the initial idea of building a total of 7 luxury towers in the Jordanian capital.

The Abdali Project is arguably the most prestigious in the country. Modeled to a large extent on Solidere’s downtown Beirut project, it aims to become the new (commercial) heart of Amman. Its failure would be an absolute disaster for Jordan’s international standing. It remains to be seen however, if the project will finally be executed as planned on the drawing board.

A planned university and medical city, reportedly, have already been cancelled. In the project’s $2 billion second phase are another nine high-rise towers and 25 mid-rise buildings. Seeing the fate of the twin coffins of the Royal Gate — and the many, many other plans to build Jordan’s biggest this and tallest that — perhaps a slightly humbler version is not entirely out of place.

BOX Saraya dream turns sour

A little Dubai dream on the coast of Aqaba

The Lebanese daily Al Akhbar reported on February 13 that King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia had saved Saad Hariri from bankruptcy by offering him a $2 billion interest-free loan. The latter firmly dismissed the report as Hezbollah propaganda. True or not, rumors over Hariri’s financial health have been persistent and if his real estate endeavors are anything to go by, then a major Saudi bailout would not come as a surprise.

Saad Hariri is the chairman and majority shareholder of Saraya Holdings, a Dubai-registered firm that aims to develop “luxurious mixed-use tourist destinations”. Its first and flagship project was announced in May 2005 at the World Economic Forum: Saraya Aqaba, a $1.2 billion mixed-use resort built around a man-made lagoon. In partnership with, among others, Arab Bank, the project had an initial capitalization of $242 million. It raised a further $120 million by issuing shares.

Other project announcements followed in quick succession. In September 2005, Saraya Holdings, Arab Bank and the Emirate of Ras Al Khaimeh signed an agreement to launch the $500 million Saraya Islands. In February 2006, Saraya and Arab Bank launched a $250 million real estate investment fund. In June 2006, Saraya signed a deal with Oman to create a first-class beach resort south of Muscat. In 2007, it announced a deal to create a $700 million Dead Sea resort and a luxury resort on Russia’s Black Sea coast. Then came the ‘Big Bang’ of 2008, and suddenly things turned very silent indeed at Saraya Holdings. Work at Saraya Aqaba, by the construction arm of Hariri-owned Saudi Oger, had started in January 2006 but was stalled in 2008. Executive requests to Saraya Aqaba for further information on the matter were declined.

Last year, a former Saraya employee told Jordan’s Jo Magazine that Saraya Aqaba’s business model was based on one-third equity, one-third loans and one-third pre-sales. A model quickly undermined, he said, as the project’s estimated cost ballooned from $700 million to $1.2 billion. “The company grew incredibly quickly,” said a prominent Jordanian contractor and former employee of Saraya Aqaba, who wished to remain anonymous due to fears public comments could jeopardize his business. “It seemed they were trying to inflate the brand name in order to go public. Then the crash happened and we had to scale back dramatically. The marketing department in Amman alone went from thirty-five employees to just four or five. We thought it would get better, but the CEO, Ali Kolaghassi, eventually admitted that it wasn’t looking good — and that’s when many of us lost our jobs.”

While most Saraya projects are “on hold”, there is a chance that Saraya Aqaba will still rise from its coma. In October 2011, the company announced a new cash injection of $240 million by an unnamed Abu Dhabi investor, which follows a previous $350 million injection by Saraya Holdings’ Aqaba partners Arab Bank, the Aqaba Development Corporation and Jordan’s Social Security Corporation.

By February 2012, with work at Aqaba still yet to be resumed, the company issued a rare press release promising to begin discussions with clients who had bought homes in Saraya Aqaba. “We do appreciate the patience of our customers and look forward to addressing their needs within the coming weeks,” wrote Saraya Aqaba’s general manager, Saud Soror. Whether that means Saraya’s dream world of villas, townhouses and a lagoon will indeed manifest, one can only wait and see.

EXECUTIVE MAGAZINE;

March 9, 2012