MIDDLE EAST EYE; Sept 2, 2017

Text Peter Speetjens

What’s a life worth? That is the question that came to my mind when Canada’s Supreme Court awarded former Guantanamo Bay detainee Omar Khadr $8.4m in damages earlier this summer. It produced a wave of moral outrage in Canada and the United States: how on earth could one ever reward a “terrorist”?

One poll found that 71 percent of Canadians thought the authorities should have continued the legal battle, which prompted Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to make a public statement explaining how an appeal would only postpone the inevitable and cost even more taxpayers’ money. The lawsuit was simply unwinnable.

As emotions ran high, the many inconvenient truths concerning Khadr’s case were easily overlooked. Most importantly, he was only 15 years old when his father, whom the Canadian and US governments have accused of being a senior al-Qaeda associate, took him to Afghanistan in 2002. Shortly after arrival, he was severely wounded in a firefight with American troops and taken captive.

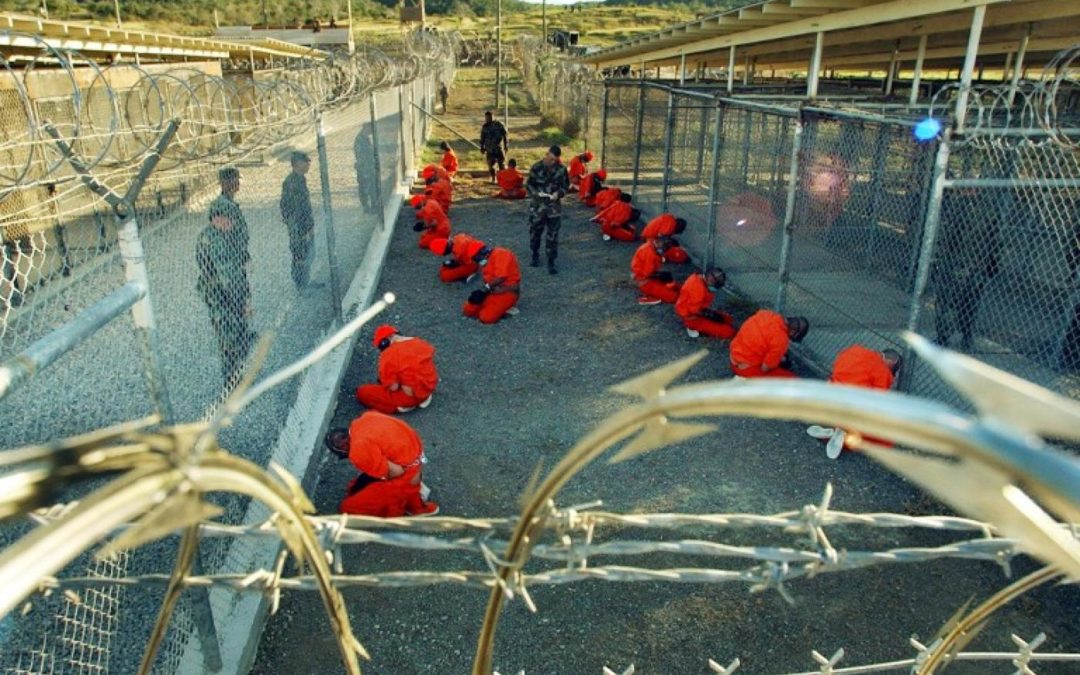

The next 10 years Khadr spent in an orange jump suit in Guantanamo Bay. Khadr was, in fact, the youngest of the 780 prisoners in the American Gulag, a legal black hole that violates just about every principle of what constitutes a fair trial.

In addition, Khadr was subjected to a regime of severe sensory deprivation and physical abuse. Details of his ordeal make for very grim reading indeed.

While in captivity, Khadr sued the Canadian authorities for having failed to seek his release and repatriation and, worse, for actively participating in the reign of terror at Guantanamo Bay. On several occasions, Khadr was interrogated by Canadian intelligence officers.

Legal subtleties lost

From a legal perspective, Khadr’s case really was clear-cut from the start. As a Canadian citizen, Khadr is protected under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which includes the guarantee of being presumed innocent until proven guilty in a fair trial.

From a legal perspective, Khadr’s case really was clear-cut from the start. As a Canadian citizen, Khadr is protected under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which includes the guarantee of being presumed innocent until proven guilty in a fair trial.

As a minor, Khadr was also protected under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states that all children under the age of 18 caught fighting should be treated as “victims,” not villains. Both Canada and the US are signatories to the treaty.

It should, therefore, hardly come as a surprise that the Canadian Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s verdict and concluded that the Canadian government had “actively participated in a process contrary to Canada’s international human rights obligations and … contrary to the principles of fundamental justice”.

Not helped by an increasingly populist press, such legal subtleties were largely lost on the general public, which was further blinded by the circumstance that, in the firefight preceding his capture in 2002, Khadr had allegedly killed sergeant Christopher Speer and wounded sergeant Layne Morris.

Lying wounded on the floor, Khadr purportedly lobbed a grenade at a group of encroaching soldiers. Khadr admitted as much when he finally appeared before a military court in October 2010 and pleaded guilty to “murder in violation of the laws of war” (war crimes). A few years later, however, he claimed he had only confessed to the charges because he was promised a reduced sentence and transfer to Canada.

Surreal turn of events

His confession – true or not – produced yet another surreal turn of events. For, while Khadr had sued the Canadian government, Christopher Speer’s widow Tabitha and Sergeant Morris had sued him in a civil suit in Utah in an attempt to receive compensation.

Aided by the military verdict, the Utah judge in 2015 held Khadr responsible for war crimes and awarded Speer and Morris damages worth an incredible $134m. When the Canadian Supreme Court awarded Khadr $8.4m this July, Speer and Morris immediately tried to freeze the amount – in vain.

Now one should know that war crimes consist of two main categories. The first deals with major crimes against civilians. Think massacres such as Srebrenica. The second bans the maltreatment of enemy soldiers and prisoners of war.

Even if Khadr threw a grenade at a group of invading soldiers, it seems rather far-fetched to perceive that a “war crime”. In fact, if there is any war crime that plays a role in Khadr’s case, it is the American treatment of him and other inmates at Guantanamo Bay

None of the above was particularly upsetting to the morally outraged, some of whom started a fundraising campaign on behalf of Khadr’s presumed victim: Tabitha Speer.

Pay out hypocrisy

To put things into perspective, it is revealing to see how the US army deals with paying damages. First of all, it makes a strict distinction between civilians and combatants. The latter are never, ever compensated.

Regarding civilians who fall victim to US military operations, there is no law or treaty that compels the US to compensate, but ever since the Korean War it has made so called “condolence payments,” which are meant to help ease the pain and suffering due to the loss of a loved one.

These payments were introduced in Iraq shortly after the 2003 invasion and in Afghanistan in 2005, ironically, just after the Taliban started to compensate people who had fallen victim to American bombardments.

In March, Reuters obtained military documents under the Freedom of Information Act, which showed that, between 2013 and 2016, the American armed forces had paid Afghan families $1.2m for a total of 101 people killed and 270 injured. That is an average of $3,234 per casualty.

In the case of the notorious 2015 bombardment of a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, which left 42 people dead and 37 injured, the US army apologised and offered $6,000 to the families for every person killed and $3,000 to anyone injured.

The moral outrage regarding Omar Khadr’s case makes one thing painfully clear: the functionality of man’s moral compass is severely hampered by the notion of distance and next of kin. The “closer” disaster strikes, the louder the call for justice, the higher the compensation.

While this phenomenon may be perfectly understandable from a psychological perspective, it is painfully hypocritical from a legal and ethical point of view to the extent it makes one wonder if indeed all men are equal before the law.