This month 150 years ago, Mark Twain left New York aboard a retired Civil War vessel named The Quaker City for a “pleasure trip” across Europe and the Middle East.

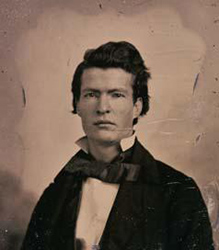

Aged 32, Twain was not yet the Twain we know today. Born in 1835 as Samuel Clemens, he was a young journalist with literary aspirations. His novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer only appeared in 1876. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn followed eight years later.

By no means a rich man, Twain convinced a Californian newspaper to pay for his travel expenses, which amounted to some $1,250 (some $20,000 today). In exchange, he wrote a series of articles on The Quaker City tour, which in 1869 were bundled and published as The Innocents Abroad.

The book became an instant bestseller. It is quite different from the many travelogues published in the course of the 19th century.

“This book is the record of a pleasure trip,” Twain wrote in the foreword. “If it were a record of a scientific expedition, it would have about it that gravity, profundity and impressive incomprehensibility which are so proper to works of that kind.”

A grand tour along the sources of Western civilisation had been a la mode for the 19th century European elite for years, yet this was the first such a trip from the United States.

That is not to say the book lacked a higher purpose. Twain aimed to suggest how the American reader would perceive Europe and the East “as if he looked with his own eyes instead of the eyes of those who traveled before him”.

Hence the title The Innocents Abroad, which includes Twain himself. For unlike most European travellers in those days, Twain does not present himself as “the expert” unveiling and explaining the wonders of the world. On the contrary, Twain quite happily presents himself as a layman.

Equal opportunity wit

The Innocents Abroad is a critical account of the burgeoning tourist industry and arguably the first modern travel book. Putting the writer and his experiences at the centre of it all, it quite effortlessly alternates personal and historical anecdotes with descriptions of people and lands.

The Innocents Abroad is a critical account of the burgeoning tourist industry and arguably the first modern travel book. Putting the writer and his experiences at the centre of it all, it quite effortlessly alternates personal and historical anecdotes with descriptions of people and lands.

Last but not least, Twain injected the book with a healthy dose of irony, which may not surprise the readers of his later novels.

Typical Twain is the following description of Civita Vecchia, a small coastal town just north of Rome: “[It is] the finest nest of dirt, vermin, and ignorance we have found yet, except that African perdition they call Tangier, which is just like it.”

Twain’s biting wit is also what makes the book controversial. Critics have accused Twain of “Western superiority”. Others even claim he is racist and anti-Muslim. At first sight, there is something to say for that.

For example, when Twain visits the “old fossil” Damascus, he wrote its inhabitants were “the ugliest, wickedest looking villains we have seen”. In Morocco, he states that “the Moors, like other savages, learn by what they see; not what they hear or read”.

Twain surely is not always the subtlest of voices, but it is too easy to accuse him of false superiority, racism and bigotry. For Twain’s pen targets everyone. Upon arrival in the Azores, for example, he writes: “The community is eminently Portuguese, that is to say slow, poor, shiftless, sleepy and lazy.”

When in Constantinople, he writes that the Greeks, Turks and Armenians all like to attend church on Sabbath only to breach each of the Ten Commandments the rest of the week. However, according to him, the Greeks were by far the worst cheats of them all.

What’s more, Twain had the same critical eye and sharp pen when depicting his fellow passengers, most of whom are of the religious and predominantly interested in visiting the Holy Land. Hence the book’s full title: The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims’ Progress.

When in Constantinople, he notes that the Ottoman Sultan has 800 wives, which – with a sublime feel for understatement – “almost accounts for bigotry” and would make “our cheeks burn with shame”. However, “we don’t mind it so much in Salt Lake”.

Upon leaving Damascus, he also wrote: “But of all the ridiculous sights I ever have seen, our party of eight is the most so – they do cut such an outlandish figure.”

With their white umbrellas and white rags wrapped around their hats, their stiff knees and flapping elbows, they were “the worst horseman gang on earth”. Twain was amazed the gods had not got out their thunderbolts to destroy them and he himself would never have them through any country of his.

The unlearning of Twain

Finally, as in any good travel writing, Twain had to face his own preconceptions. Or, as Twain puts it, he had to “unlearn” things. So, he is quite disappointed with the size of the Holy Land.

“The word Palestine always brought to mind a vague suggestion of a country as large as the US,” he wrote. “I suppose it was because I could not conceive of a small country having such a large history. Yet in reality it hardly covers an area equal to four of our counties of ordinary size.”

It makes him wonder how “great” the many kings mentioned in the Bible actually were. Which brings me back to Twain’s main aim: he wanted the reader to look “as if he looked with his own eyes instead of the eyes of those who traveled before him”.

For too often he found that his fellow travellers were filled by prejudice and preconceptions. Too often they had a verdict about the countries they visited before even entering. Too often, they only saw what they wanted to see in order to confirm their own beliefs.

To keep an open mind, to see beyond the words used to capture countries and people, is a credo that has lost nothing of its urgency in today’s increasingly polarised world.

It is one reason to still read a book that is almost 150 years old. Another is to get an idea about a world that once was. And yet another is just to have a good laugh.

MIDDLE EAST EYE

June 14, 2017